On inviting an AI onto the stage

I really do not want to write this. Simultaneously, I must.

Writing this draws attention to a phenomenon I strongly dislike, but without writing it, these concerns remain internal: undiscussed, uncriticised. Even with a severely critical tone, releasing text publicly gives credence to this topic, which is both something I want to do for the sake of discussion and also badly want to avoid to prevent the propagation of the behaviours which involve it. In other words: ‘there’s no such thing as bad publicity.’

Last night, I watched an AI-adjoined contemporary music concert. Despite the humans’ masterful playing and some interesting compositional ideas, it was oddly unpleasant, and the indisputable highlight of my night was running into an old friend whom I hadn’t seen in a good five years in the bathroom and giving her a bear hug before she even got to wash her hands. (I’ll come back to why this is important later.)

The first half of the gig was a handful of new pieces for modular combinations of percussion, keyboards/electronics, and voice that somehow integrated the use of AI. The second half was a song cycle (2 percussion, 2 keyboards, and voice) for which all the text was generated by an AI.

To avoid barfing all my thoughts onto your screen, I’ll focus on one piece from the first half. The composer introduced it roughly like this: “I invited an AI to perform on stage with the Riot Ensemble. However, this AI only knows how to play music in the style of J. S. Bach.”

The first note of the piece was the pianist picking up the sheet paper in front of him, turning to the audience, and ripping it.

The AI had no clue what to do with this sound. Johann would.

It is unclear to me which came first: the quartet composition or the use of a Bach-y AI (I’ll call it Baich). The direction here would provide critical information to the audience: if the quartet came first, then is the interjection of Baich simply a curious little experiment to see whether it knows what to do? Is this a question being posed to Baich? Or, if the direction were the reverse (Baich, then composition), why was a musical decision made for the first note to be what it was?

I am one of the most pro-ripping-paper-on-stage-as-a-musical-act people that you will ever meet but this doesn’t mean I believe weird shit belongs on stage for its own sake. Conversely, I won’t assert that there must be a reason, I am also fully aware that people just do things and shrug their shoulders when asked why, then do another thing. I don’t know the composer who wrote this music, so understanding her and her musical utterances would help me here, but it's good fun to poke at this before changing my mind due to uncovering how thoughtful she is. (Edit: I caved. Her name is Megan and here is her description of the piece https://megansteinberg.com/2023/05/03/new-inventions-for-riot-ensemble/ )

If composing a score which incorporates ripping a sheet of paper were an intentional move – what is this intention conveying? Is it simply saying: “this is the type of music where we rip paper on stage because I’m the type of composer in the type of musical niche that does that sort of thing,” which would be appropriate in the direction of quartet followed by Baich… but in which case, why was Baich selected as opposed to a differently trained AI? Or, does it say: “the ridiculousness of ripping a piece of paper in the context of a piece that’s supposed to sound like Bach is an intentional act which conveys this extreme diversion from music that is rooted in figured bass. This is a-harmonic, a-melodic, a-structural riot music.” In the latter, Baich before composition would be the logical direction.

Furthermore, I’m not convinced that Baich knew nor understood figured bass.

The way that APIs which identify music work (e.g. Shazam) is that they create a “fingerprint” of a recording. This fingerprint is something like the squiggly lines you see when you’ve recorded your 137th take of Lt. Kijé (for those who don’t know, insert any orchestral excerpt, or whatever music you play and record and naïvely hope to perfect) into ProTools or Logic or whatever, and then cringe a bit when you see how laterally imbalanced your hands still are despite continuous efforts otherwise. It’s a bit more multi-dimensional than that, but for simplicity’s sake, let’s use this model. It takes that fingerprint and then matches it with all the recordings in its database to identify what the fingerprint probably represents.

I have no idea how AIs work (yet am unafraid to talk about this, because it turns out, even the people making them don’t), but let’s imagine that this Shazam API process is the first half (input) of Baich. Thus, Baich was fed all the possible recordings of Bach’s compositions that the engineers could collate. Then the output is some sort of neural network processing that runs bunches of numbers through bunches of digital ‘neurons’ at ridiculous speeds and manages to come up with a probability for what the next output should be and executes that output in cases where the probability is as close to 1 as possible.

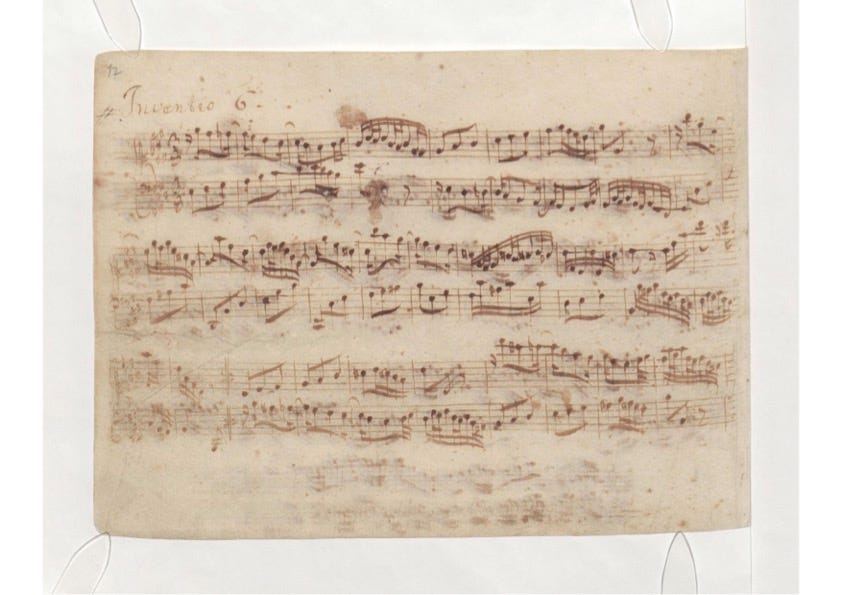

Whatever Baich was doing, or however it was doing it, the output, once it finally received a stimulus it could respond to (something the players played which had pitches and pulsed rhythms, so, not the initial paper rip), sounded like a continuous string of fragments of sounds similar to actual Bach excerpts. For example, it overtly spat out an excerpt of the first four bars of BVW 777: Invention No. 6 in E Major. This may have been transposed to fit the previous and subsequent fragments, but it was inarguably Invention 6.

Playing four bars of a composition, even if you can transpose it, play it in retrograde and invert it, is not the same thing as playing four bars in the style of a composition. Just about any human with intact fingers can learn that invention if they put the hours in (there are many methods: by rote, with a teacher, using the symbols on the page if you know how to interpret them), but this is not the same thing as interpreting each chord used in the piece and how these chords relate to one another, then transmitting a new musical gesture that is informed by this understanding. This requires an in-depth understanding of music theory and how chords and rhythms relate to one another. This is generalised knowledge. (There are AIs which understand, or appear to humans to understand, harmonic and rhythmic relationships, but, as far as I am aware, none yet integrate these and go a step further in analysing and interpreting Bach’s music)

With this grounding, a human can then analyse the invention and reduce it down to a harmonic structure. Although the patterns Bach used are well agreed upon (and I’m not a Baroque scholar so if you are please scream at me in the comments), there remains subjectivity in this process, thus interpretations of this music can vary to some extent. They could then use this subjectively-derived harmonic structure to improvise, assuming they also have knowledge of chord-scale relationships (and which relationships are appropriate to apply in the context of Baroque music). However, at this stage, it is no longer the music of Bach, it is a musical adaptation of the style of Bach, emitted by that human, which is an exceptionally special thing that integrates the knowledge, ability, and intuition of the human who is creating it.

It is possible to argue that there are some numbers which can explain all of this, and we just haven’t figured them out yet. We can attach numbers to all of the neurochemical and environmental elements associated with this human’s interpretation and utilisation of a Bach composition, and assuming we know what those numbers are and that we can assign formulae to them which explain every element of the process, we would then have the power to predict how that individual would play ‘in the style of’ Bach note for note. We can’t do that yet and we are nowhere close.

(If we could do that, then, it would seem reasonable that a Turing Machine could gather such numbers for a minimum number of individuals to understand all the possible variations of human musical expression in the style of Bach, then operationalise this knowledge by creating an AI that does the same thing as a randomly generated human could. But, again, we are nowhere close to this.)

To set the numbers aside for a bit, the human is not (consciously) using any numbers to do this. They either do or don’t know what they’re doing and just exhibit some behaviour that results in music ‘in the style of’ Bach, in as informed and effortful a way as they can. The reason why they do it is almost as interesting as the result itself.

But Baich plays ‘in the style of’ Bach using a completely different method. And the result is strings that are probably more self-consistent than what the human would do, but which fail to grok Bach’s music. They sound like an empty, linear emission that is technically impressive but void of a wholeness.

Let’s now reimagine this composition, in both possible directions, with a keyboard-playing human who’s a Baroque expert in place of Baich. We’ll name this human Jumana.

Jumana has joined Riot Ensemble for a gig as a featured improvising artist. In one possible version, Megan has written a quartet for Riot Ensemble and simply instructed Jumana to improvise throughout.

This next bit is going to be impenetrably circular: I’m not Jumana, in fact, she doesn’t exist, but if I were, and I saw and heard the first rip followed by subsequent rips combined with drum kit figures played with rutes that opened the piece, I might have contributed by lightly scraping the keys in a glissando motion with the backs of my fingernails in a steady rhythm which fit into everyone else’s. This rhythm would play homage to Bach as his were plain and steady, but the timbres would match the ensemble’s. Thus, it would be an expression in between the two worlds: Bach’s music and Megan’s quartet, which would be musically and contextually informed due to my ability to generalise the knowledge from both these worlds.

But, Jumana probably wouldn’t do this unless she were me, because she’s not a percussionist reasonably well-versed in manipulating odd objects in ways orthogonal to their intended purpose. It’s hard to imagine being Jumana (which is why this part is circular).

As the piece continued, Jumana might contribute with contrapuntal figures that were reasonably in tune with the harmonic elements of what the quartet was playing. She would also take some pauses and listen, as good improvisers do. She might interject direct quotes of existing compositions, as Baich did, but would do this from a different, intuitive foundation that draws upon a wealth of experiences of playing real music on real instruments in the real world.

To be honest, I’m not sure whether Jumana would have even agreed to play this gig. She’s mastered a particular thing and this is an unrelated context from one she normally engages with. Let’s pretend Riot Ensemble offered her enough money (millions of dollars?) for her to have said yes and move on.

In the second scenario, Jumana is improvising however she ordinarily does in her usual context, and Riot Ensemble uses paper-ripping material among the rest of the compositional parts of this piece to accompany. This scenario does not start with a paper rip, as Jumana’s playing would be unlikely to start with a paper rip.

One final possibility here is that the paper rip is an imagined scene in Bach’s life where he was composing and unhappy with his output. But if this were the case, it was not expressed in the music nor its description.

The challenge here is imagining a piece of music that somehow had a reason to integrate figured bass improvisation with paper rips. Megan writes in her description of the piece that it showcases the limitations of AI, and with this intention, the piece did a good job of that.

However, beyond that, I’m stumped. My questions move beyond this composition as simply an exercise in integrating AI into live performance.

- Did the use of AI somehow make this music better?

- Did the use of AI showcase something that humans could not do?

- How is the composed material a statement on AI? Is it a ridicule?

- Does the limited output of the AI expose the limits of the composition itself?

Back to the bathroom: after Naomi and I expressed how happy we were to see each other, she decisively said to me on our way out of the bathroom that she was against all use of AI.

I join Naomi when I answer the first two questions with a decisive no. The answer to the third was attempted earlier. The fourth question is a bit more nuanced.

Throwing Baich into this quartet allowed another layer of music to be added to it but did not seem to enhance its meaningfulness. Due to this, it seems that throwing Baich into any composition is just a means to accomplishing something quicker, with a bit less effort. This is in line with increasing productivity being in vogue in our modern culture. It is also in line with the demand for pills and hacks and quick fixes, like those ads that I despise on YouTube about how there’s some new secret way to learn how to play the piano. I don’t care about that because I don’t play the thing for the sake of grasping it. I play it because of what it means to me.

I’m not saying that Megan inserted Baich into her composition to write it quicker with less effort. I have no clue why Megan invited Baich into her composition (despite having read her description). It may have been because she was paid (millions of dollars) to do it. Or another reason.

But I sense that AI is being built for these types of reasons: “let’s get more stuff done faster.”

But has this sped-up productivity made the result any better? Did it enhance the meaningfulness of the art in any way?

A deep sense of meaningfulness is not necessarily a requirement of music. All voices, musical or otherwise, are valuable and worth hearing. But at the same time, if this piece had had this, I might not have preferred a microbe-laden hug to it. This isn’t Megan’s fault. I can’t even blame Baich. I’ll pin this on the cultural (and possibly evolutionary) trends that got us into this mess in the first place: the rootless pull to increased (unfulfilling) productivity which dragged us from PCs through to Baich.